Practicing Biomimicry to Prepare Students for Uncertain Futures

This is my sixth post about our assessment system, and though there is more to say, I’m going to move onto another system after this. I’ve already written about:

—the ways we recrafted the messages that assessment sends to students;

—the major design decisions we made to build a practical, functional assessment system;

—the perils of summative assessments like end-of-unit tests;

—why we shouldn’t even bother with curriculum if we aren’t going to attend to coherence and rigor every step of the way.

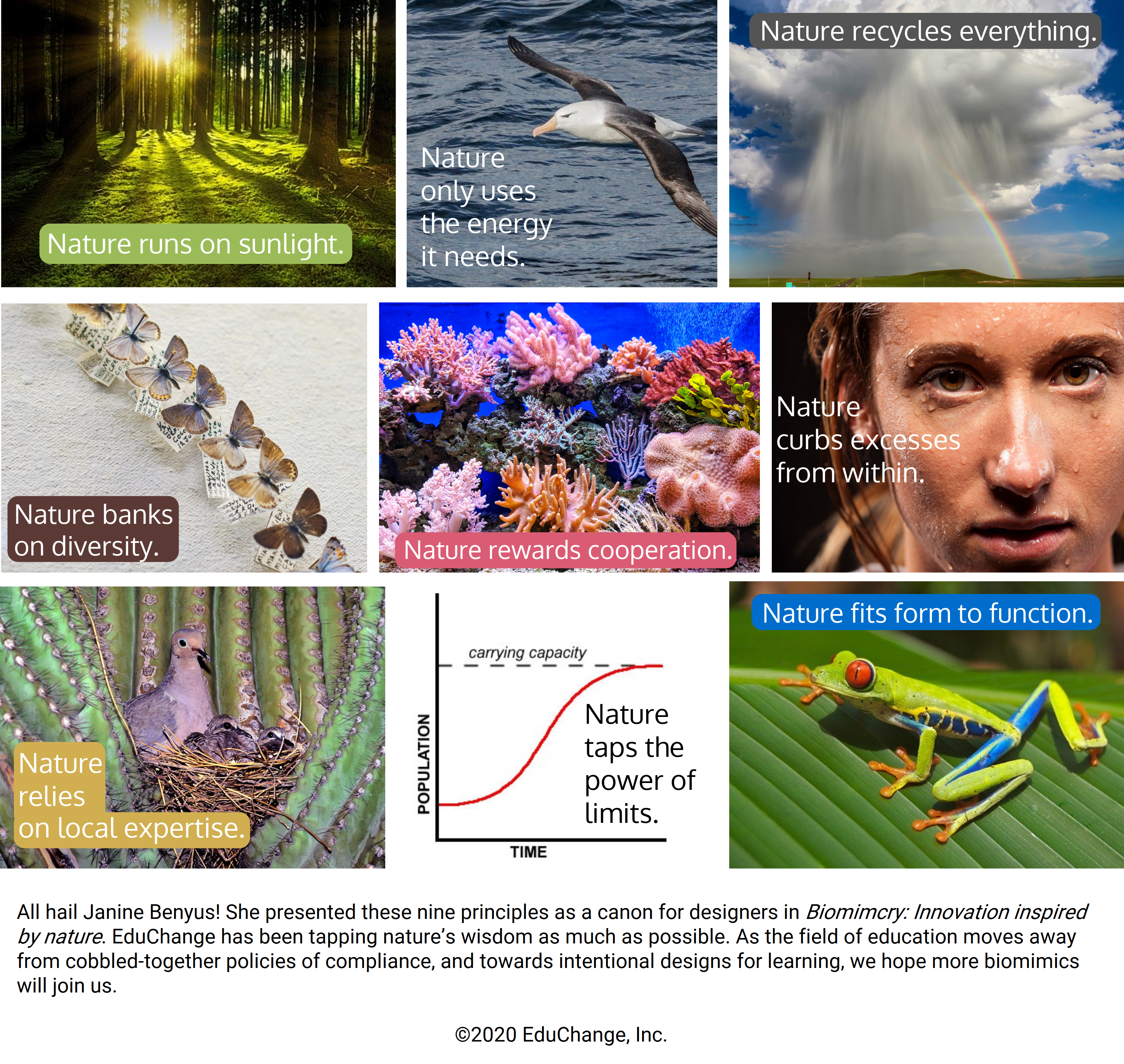

Now I’m going to share how biomimicry inspired our assessment designs…

A Healthy Dose of Humility

If you haven’t read it, I recommend Janine Benyus’ masterpiece, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature.

It hit bookshelves in my early days of teaching and its brown, curled pages still guide my thinking.

At university I studied the most elegant systems of all: living ones.

There is nothing more humbling than nature’s designs, and marveling at their beauty is my favorite meditation.

I come from a family of entrepreneurs and engineers, so I was probably destined to apply my life science studies to solve problems in education.

This Václav Havel quotation that Benyus selected for her first chapter resonates, particularly because his language speaks directly to learning and its assessment:

“We must draw our standards from the natural world. We must honor with the humility of the wise the bounds of that natural world and the mystery which lies beyond them, admitting that there is something in the order of being which evidently exceeds all our competence.”

Václav Havel, former President of the Czech Republic Tweet

Our first step with competency-based assessment was to acknowledge its limitations.

One of the many failures of ed reform was its refusal to accept the limitations of standardized tests, and a subsequent refusal to limit their role in the national assessment conversation.

The ‘achievement mongers’ discovered that the pursuit of higher test scores in closed-loop accountability cycles was self-serving—leading to more grant funding, investment dollars, and social prestige than most educational leaders had ever enjoyed.

And thus, they doubled down on preparation for tests expressly designed to marginalize the very students they were serving.

Such hubris always finds its roots in a blatant disregard for human limitations, a failure to accept, as Wes Jackson reminds us, that “human cleverness must remain subordinate to nature’s wisdom.”

There is a lot we don’t understand about the brain and learning, and educators must learn to sit with this fundamental source of uncertainty in everything we do. We endeavored to shift the purpose of assessment and offer this uncertainty a seat in our classrooms.

An assessment system should be regarded not as a nexus of power, but rather as a toolkit for observation, conversation and reflection.

I believe that competency-based assessment conversations can be both constructive and compelling, but only after we avow that student performance on a set of related tasks is only partially descriptive, and may not capture all that is invisibly incubating.

Given our constraints as educators, we should strive to use as much data as possible to describe performance against an expectation that is reasonably small and well-defined. In our program, we carved out a lot of practice time and offer students multiple opportunities to demonstrate proficiency.

This felt like a practical way to honor all that a single task cannot completely describe about a student’s position in his/her/their learning process, while still providing that student with guidance for improvement.

We’ll let you know when the next post is ready for you!

In a previous post I described why we eliminated all summative assessments. We replaced them with reasonably-spaced tasks that serve not as power tools but rather as conversation starters, first as part of a learner’s own dialectic and then to spark dialogue with the teacher.

Conversations about performance on rich tasks can clarify, encourage and motivate when they are not silenced by an all-encompassing grade.

This evolving conversation should parallel the learning while disrupting it as little as possible. That happens only when the entire assessment system sends the right messages consistently.

Assessments should help classroom communities observe the fits and starts of competency-building, not control them.

Authentic observations of a work product in the world of STEM underscore peer review, a process we emphasize to help students understand the vital role that peers will play in their lifelong learning process.

But feedback in and of itself is not an assessment panacea. Feedback fuels growth only when all of these are true:

- students understand how feedback supports next steps on a particular competency;

- students appreciate that variables outside of the defined expectations may be influencing their progress;

- multiple opportunities to improve performance (thus, multiple data points) are offered over an extended period of time, and strategically placed so students do not feel like they are ’starting over’ each time; and

- task design ensures that students can apply prior feedback to successive tasks, thus validating its utility, even as content changes and difficulty level increases incrementally.

Students will trust their own growth if all parts of the assessment system work in concert, if measurement limitations are transparent, and if the system patiently accommodates the realities of human learning.

As I’ve said before, our main goal with competency-based assessment should be for students to trust themselves as learners.

Inspiration from Immunity

There is a lot of talk in education and workforce training about the future of work. Next-generation jobs and entirely new industries will emerge after students have left school.

Will they be prepared? Will they be resilient in the face of unprecedented technological and societal change? What can schools do?

When I think about preparing to tackle the unknown, I think about none other than our immune system.

Immune cells respond daily to previously unidentified threats before they overtake healthy cells in large numbers. Most of the time our innate immune system handles any problems without much trouble. Occasionally, the more sophisticated response of adaptive immunity is required to restore order, or homeostasis, to the body.

The modern human immune response is complex and began its storied evolution approximately 500 million years ago. Just a few of the premises of adaptive immunity provide plenty of inspiration for biomimicry. I borrowed some to guide the design of our assessment system.

In basic terms, the adaptive immune response builds antibodies that attach to immune system cells and also attach to the target antigen (bad guy).

Thanks to evolution, we are born with a library of genetic instructions that we use to manufacture these antibodies as needed.

Here’s the kicker: antibodies work because they are built to fit specific targets, even those unknown to the planet at the time of our birth.

We are equipped to respond to future uncertainties because our immune cells can recombine pieces of an existing, stable genetic knowledge base to make brand new things using raw materials that we have lying around.

It’s a mind-blowing demonstration of orchestrated resilience.

And it’s exactly the kind of response our students need to mount as their uncertain futures unfold.

Consider this loose analogy: a student’s cognitive environment includes the Information Age and its surrounding social psychology.

Clusters of information—good and evil, supportive and destructive, correct and erroneous—continually swirl around this environment, looking for hosts to which they may attach.

If ideas, inventions or insults do not take hold, they amount to little more than noise. But those that find a way to ‘infect’ enough of society will gain power—perhaps as a new technology, industry, or social movement.

People who can respond to such a shift with relative ease, who can recombine their knowledge and know-how to attach and detach effectively, will be able to adapt and move forward.

And this is why the immune response provides a powerful model for equipping students for the future of work and world.

Here are some of the small ways we mimic adaptive immunity to great benefit:

- We intentionally select content slated to evolve.

By driving content organization with global issues that are situated in the Information Age, we force all stakeholders—our own designers as well as the teachers and students we serve—to grapple with novelty.

About 15% of our four-year program is new annually.

- We respect longevity.

Nature selected a library of antibody-building genes based on their proven evolutionary track record.

We established a stable library of competencies grounded in long-standing learning research and workforce needs. As educators know, so-called 21st-century skills have been serving humans for well over a century.

- We attend to competency quality and quantity.

Nature selected the most advantageous genetic complement to steer the immune response, ensured that the library was large enough to make recombination powerful, and curbed excess.

We followed suit.

Our competency library remains stable throughout our program, includes only those competencies used repeatedly in classroom practice and tasks, and is robust enough to handle emerging state-of-the-art educational technologies, STEM advancements and evolving global research in novel performance task designs.

In nearly two decades, we haven’t met new content that has rendered our system obsolete.

- We transparently model recombination for students.

Students revisit the same competencies in different combinations when they encounter each quiz or assignment.

Over time, they see how a single competency can be put to work in different ways and with varied content.

We occasionally prompt students to reflect on this combinatory process to help them build confidence to do the same when a situation warrants it.

Looking for design solutions in the natural world that might support learning in diverse classrooms is both a rare and obvious strategy.

I’ll conclude with the wisdom of Janine Benyus: “I believe we face our current dilemma not because the answers don’t exist, but because we simply haven’t been looking in the right places.”

Suggested Citation: Saldutti, C. (2020, February 12). Practicing biomimicry to prepare students for uncertain futures. 1-2-3 Learn: EduChange Design Blog. https://educhange.com/biomimicry