Heed the Science, Break the Vicious Cycles

Inequities & Vicious Cycles

Assessment practices that tend to begin in middle school core curriculum reach full throttle in high school and persist through tertiary education. The practices create a vicious cycle that defeats the psyche of many students, effectively disabling their dispositions for lifelong learning.

Several scholars have documented this cycle and its consequences. Why is assessment so fraught in high school and beyond, and how can we correct it? As described in my first post, it is important to get the beat of the system in its pure, unaltered form before attempting repairs.

In this post I’m avoiding a discussion of standardized tests; that ground has been trod. I’d like to share our observations of the flaws within conventional unit or project structures many educators use to design curriculum. Over two decades of work in 1100+ secondary classrooms have helped us identify the main culprit: the tight coupling of high-stake summative assessments at the end of units/projects with the relatively short amount of instruction and practice that precedes it.

Course designs that introduce certain concepts and skills in units or projects, and use high-stakes summative assessments to determine mastery after only a few weeks, are fundamentally inequitable.

They contradict everything we now know about how adolescent brains develop.

A unit that demands content mastery by its conclusion may appear neat and orderly inside a planning template. But in practice, the tight coupling of content & assessment within a single unit or project derails authentic learning.

If we say we believe in equitable supports for diverse classrooms, we must abandon the learn-it-and-leave it model of course design forever. Let’s see why it fuels vicious cycles…

In the previous post I discussed the undue pressures of content coverage within too-short timeframes. Those pressures force course designs into serial one-and-done units and projects that fail to revisit meaningfully the same concepts and skills in successive units.

To prove that students have met the requirements of the course, whose syllabus is often determined at the state and national levels, educators double down and create high-stakes summative assessments that demand mastery-level performance for content introduced two weeks ago.

Students who fare well earn grades that describe ‘achievement’ but not learning.

Those who don’t make the grade suffer irreversible, high-stakes failure for a given topic or historical period. And being absent from class for longer than one week is a nearly insurmountable handicap.

Regardless of student outcomes, assessed content is shelved and new content is introduced. In this way, conventional high school and university course designs ignore the experience of its stakeholders.

Courses literally proceed in spite of those enacting them.

So which high-stakes assessments are worse for students: the standardized versions deployed annually by external entities or those they endure monthly as part of their classroom experience?

- a) fall further behind with each successive unit;

- b) decide that gaming the teacher’s system will be more beneficial than actually learning the material;

- c) cheat habitually or as needed, to include over-reliance on tutors;

- d) disengage and shut down; or

- e) enjoy high grades without deep conceptual understanding or truly portable skill proficiency.

Any of these predicaments can be anxiety-provoking, stressful, demoralizing or frustrating. Indeed, none foster lifelong learning dispositions.

The unnatural—and largely unuseful—act of forced memorization within too-short timeframes is awarded with high grades that represent ‘achievement.’

And our course designs are to blame for this distorted message about how learning happens. Always rushed down a linear path, students construct an erroneous relationship between time and learning that worsens as they age.

The Vicious Cycle Churns Grief and Loss

Time is probably the biggest design constraint for academic systems. It is not uncommon or surprising for teachers to feel stressed as the summative assessment approaches, particularly if they sense that some students may not perform successfully.

And the memory of past exam failures can resurface for students, making it more difficult for them to focus, retrieve or produce on the assessment itself.

Teachers often insert review games and re-teaching activities before the summative assessment to boost confidence, yet this added time translates only to a few added points for some students. And if answers to test questions are explicitly given through review activities, it is difficult to take the assessment results as serious markers of understanding. These last-minute tactics do not ultimately support those who are too confused, too far behind, or simply disengaged.

When faced with poor assessment performance, teachers engage in triage through re-takes, redos, make-ups and test corrections. Some schools even turn these tactics into policy. The final score may increase, but student learning? Not so much.

And it doesn’t make students feel better about the assessment, either. They know they didn’t measure up the first time, and understand that the teacher’s only recourse is to provide a mechanism to ease the blow of a low grade.

While I completely understand the intent, I always find it peculiar that the part of the learning cycle that tends to be associated with negative student impacts is also the part most often extended—in the name of reducing negative student impacts.

Hmmm….

In the previous post I shared some of our findings related to time spent on various academic activities in secondary classrooms. This infographic shows that approximately 20% of class time over the course of the year is devoted to end-of-unit/project assessments.

On the curriculum map or planning template the summative assessment appears as a singular moment in the unit/project. In practice, the anticipation and aftermath of the summative assessment create backlogs in every single unit.

Delays are inherent to every system, but behaviors that exacerbate these delays are undesirable, if understandable, reactions to poor designs.

The social and emotional consequences of adding days for summative assessment triage are heartbreaking. The test performance blues overshadow the energizing, rich learning experiences the class enjoyed earlier in the unit. Additionally, this grief is compounded by one or more of the following:

- a profound sense of loss, both in terms of the lost opportunity for success on the assessment, and the perceived loss of the singular moment where true conceptual understanding eluded the learner;

- the development of a fixed mindset around certain content, leading to false declarations that ‘I’m not good at Medieval history’ or ‘I only sort of understand mechanisms of heredity;’

- the stressful anticipation of another round of blows to the psyche with the next high-stakes assessment.

Scientists now believe that our very perception of time is emotionally charged. Theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli aptly notes that “our brain is a machine designed to tell a story about the past to do something about the future…time is a source of our suffering…time, for us, is this emotional connection to the events of the world that we lose.”

Ultimately each day brings us closer to death, and we are conscious of this in ways that other species are not.

But we also have wildly different experiences with time’s passage, which can feel achingly slow or seem to fly by.

By emphasizing completion & coverage over student success, does class time feel achingly slow?

Are we marking time by what is lost more than by what is gained?

How would their emotional experience change if students knew that additional opportunities to improve performance & deepen understanding were right around the corner?

And how would class time feel if performance expectations were more realistic and not quite so punishing?

Heeding the Science

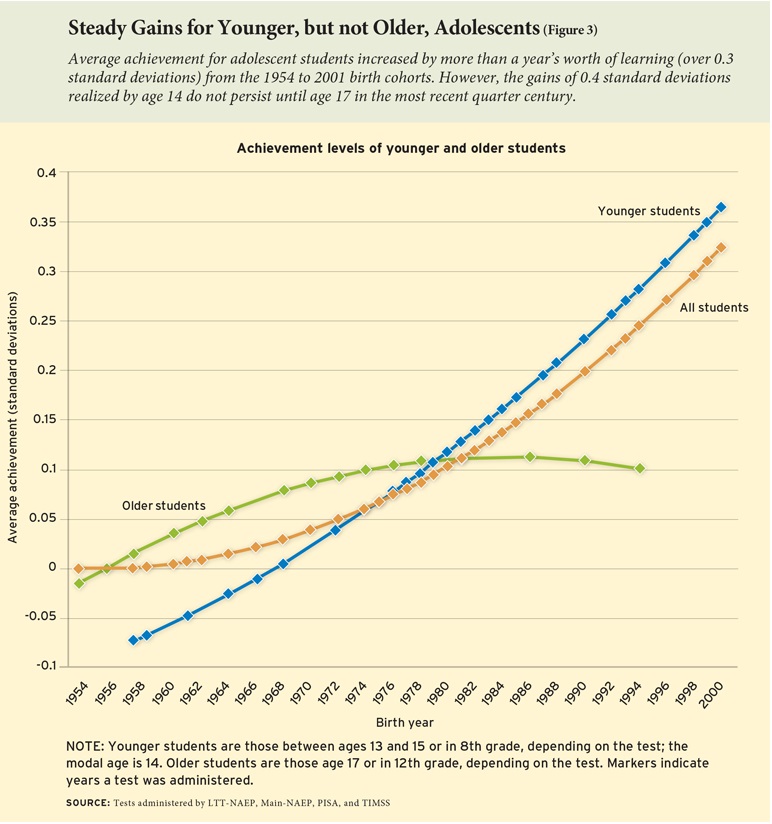

If we want to design curriculum that maps to our current understanding of how teen brains work, we must come to terms with the fact that upper secondary and tertiary courses assess for mastery prematurely.

I recommend this free online course for educators, which explores the research of Drs. Kurt Fischer, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and others. They describe how conventional curricular designs adopt an unnaturally rigid ‘learning as ladder-climbing’ model.

In reality, people construct dynamic webs of connected skills that branch and grow at different rates for different people, and according to their emotional state.

While curriculum should be designed to accommodate this variation across learners, virtuous designs need not be impractical for teachers. It is beneficial for a class to engage in the same learning experiences, as many learners share branches and connections in their webs.

The key to accommodating this variation is the provision of a supportive environment, to include sufficient time:

“Learners must actively build neural networks, a time-consuming process that results from the effort required for repeated trips over the same ground—to lay out the routes, mark them, clear them, create foundations, pave them, roll them several times, connect them, and add the signs, lines, and railings that will guide us when we revisit them.”

Annenberg Learner, Neuroscience in the Classroom Tweet

This helps explain why assessing students for mastery at the end of a single unit or project is often stressful.

But also this type of summative assessment can be downright inaccurate.

With every new opportunity to apply learning, student performance can vary widely. If students are asked to apply concepts to analyze a complex data set or text, they may perform at a lower level than they enjoyed in class activities.

When this opportunity is part of a summative assessment, students are overly penalized for this performance dip. And instead of expecting such a regression, students feel like they really blew it, which is confirmed by a low grade.

No amount of verbal encouragement from the teacher can compete with the powerful messages emanating from academic course structures.

It’s time to share the question I asked ten years ago: Must the content contained in a given unit or project be assessed at the end of it?

Nope.

Our design solution begins by decoupling mastery-based assessment from end-of-unit timeframes.

Instead, assessment and instruction run side by side in parallel vessels, both within and across units of study.

And guess what?

Content integration over multiple years directly supports the strategic interleaving necessary for more natural neural networking, as well as the design of corresponding assessments.

Stay tuned as the designs unfurl…

Suggested Citation: Saldutti, C. (2019, September 9). Heed the science, break the vicious cycles. 1-2-3 Learn: EduChange Design Blog. https://educhange.com/viciouscycles

We’ll let you know when the next post is ready for you!