Changing Our Relationship With Content

Measuring the Stock of Content Knowledge

Particularly in high schools and universities, content knowledge has served as the stock in the academic system for a very long time. Stock in a system is like capital, the resources or materials that flow into and out of a system at different rates depending on the conditions.

It is possible to consider the amount of content in a set of curriculum standards, within a single textbook, or as prescribed by a syllabus in some sort of quantifiable way. The more content covered per unit time can lead one to believe that a course is more ‘difficult,’ but all concepts are not created equal. Some take more time to process, require several introductions across different contexts or examples, and may be understood differently or to different degrees depending on the learner.

The human brain’s interaction with content has, I fear, been largely forgotten or unexplored in most academic course designs.

Some educators, test designers and policymakers think they know what it means for an ‘average’ human learner to demonstrate understanding. They further believe they can measure a reasonable amount of a student’s stock of content knowledge through on-demand exams.

If we are honest, we can agree that neither standardized tests nor teacher-designed final exams are true measures of conceptual understanding. The regurgitation of definitions, dates and details is an obvious offense, but so too is the reiteration of the teacher’s analysis, evaluation, and synthesis given through lectures or notes.

Standardized tests that offer novel analytical tasks aren’t substantive enough to measure much more than critical literacy skills, which are important but do not measure deep conceptual knowledge.

It is time to concede that we have no reliable metric for quantifying the stock of content knowledge that is functionally available at a given moment in time within the volume of grey and white matter that sits between human ears.

And it is honestly ludicrous in 2019 to insist that students spend any time force-memorizing content bytes that can be delivered to their fingertips in less than a second.,

We got the content knowledge metrics wrong. Perhaps we have defined the stock incorrectly, too. So be it. Let’s end that chapter and move forward.

It’s time to explore the neuroscience of working memory, the ways in which humans build knowledge networks that they actually use, and how learners can best demonstrate conceptual understanding reliably over time.

We must craft academic structures and processes that reflect healthier relationships with content coverage.

We must consider how the brain potentially interacts, or not, with the concepts that stimulate it.

We must remind ourselves that our models are educated guesses but not a given learner’s ‘truth.’ In so doing, we may better identify the stock we really want flowing through our academic systems.

And then, perhaps, we can understand how to craft instruments to measure a modicum of the amazingly powerful and complex process we call learning.

Let me say up front that I believe in the power and purpose of content-rich learning experiences. The concepts, ideas, materials, perspectives and principles that fill many texts and fuel many solutions are essential to include in every learning experience.

Students cannot practice skills in a vacuum.

It is impossible to reason about nothing.

We value content so highly that we spent many years reconfiguring our own relationship with content within real-world schools, where Carnegie units, pre-determined syllabi and graduation requirements appear fixed.

Despite my opinions of these and other school structures, I wanted to ensure that anything we designed would help schools transition from where they are right now.

Radically different structures that only a single idiosyncratic school can implement due to unique conditions will not move the larger field forward. As skeptical as I am of cookie-cutter scaled solutions, we have proven that flexible, thoughtful, tested designs can map to diverse settings with success.

Content Per Unit Time

For better or worse, new educational models need to be trialed within current constraints and will be evaluated against at least some well-known metrics. Sometimes the most strategic maneuvers build a model that plays by current rules but challenges past precedent.

Looking closely, we found that the interpretations of the rules (e.g., people’s beliefs) were more constraining than the rules themselves. This opened up some possibilities for new designs immediately.

Nevertheless, we did find certain contradictions and impossibilities regarding the content organization of courses and degree programs that must be rectified, namely:

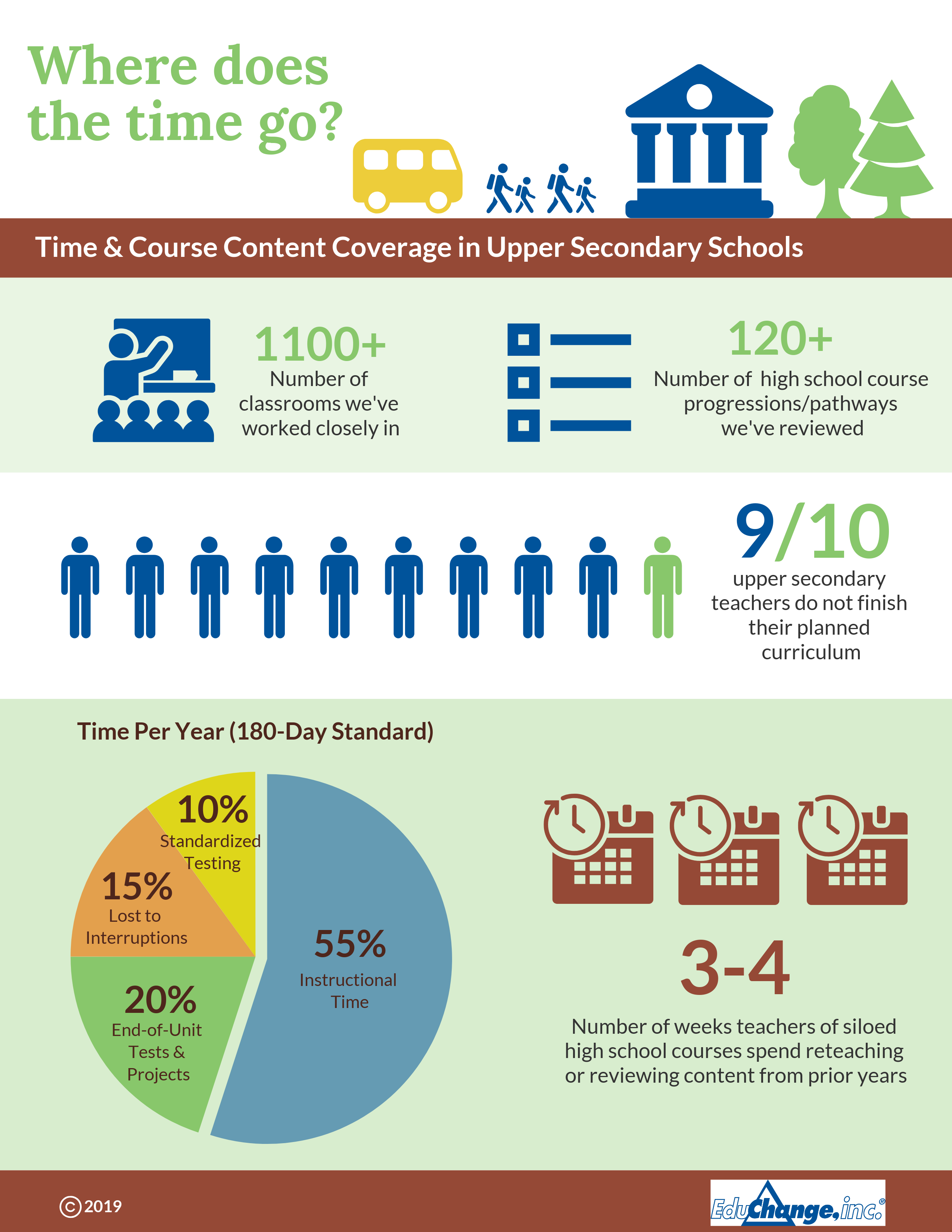

- The required syllabi of content-based high school courses within science, social studies and math (the way math is taught in high schools places it in the ‘content’ category) are either a) impossible to meet within a single year, or b) too vague and generalized to matter to most teachers.

- In places where curriculum standards and course syllabi are overloaded, nearly no teacher covers the so-called ‘required’ content within a single year. Non-covered content creates gaps in the student experience and there is no corrective loop to remedy this deficit.

- Students build characterizations of learning, as well as portraits of themselves as learners, through the paradigm of content coverage and associated forced memorization.

The fixed mindset described by Carol Dweck is partially created by this imprint of schooling that seems to harden at the secondary level and persist through tertiary education, if students make it that far.

A student’s final impression of what it means to ‘really’ learn is not the serious play of primary school, but the slog of forced memorization and teacher-pleasing in high school.

Educators everywhere know these problems have existed for years, are widespread regardless of student demographics, and plague teachers new to the classroom as well as those with many years of experience.

Despite ample documentation by well-versed scholars and nearly every teacher I have ever met, these problems are rarely addressed head-on through instructional designs, either by teachers or publishers.

I decided that EduChange needed to be different, and that meant questioning the placement of almost every brick that cobbled together our outdated academic systems.

I’m devoting an entire post to the toxic relationship between secondary schooling and time because that must change if we are going to serve diverse learners effectively.

Some theoretical physicists shed light on the fraught human relationship with time, which I will connect to the educational context.

For now, here are some hard-earned insights about the execution of secondary content coverage in practice:

- Assuming that the authors of K12 content standards have done a respectable job of delineating content that is central to the discipline (I know...but this is what teachers must accept...and frankly, teachers have difficulty removing content that these authors deem important), the most tenable approach is to expand the timeframes within which a given concept is taught.

- Through our work at the school, district, network, and ministry levels, we found patterns of wasted time and repetition as students progress vertically through a single discipline such as science. We found that purposeful redundancy was not intended, since high school teachers in different silos rarely co-design courses. Thus, patterns of lost time through the years coexist alongside the impossible task of content coverage within a single year.

- By considering science as a multi-year program of studies rather than serial siloed courses, it is possible to consider content coverage across several years. Using logic that shocks some educators, we removed the traditional teaching silos of biology, chemistry and physics, in part, to achieve more efficient content coverage.

Time & Authenticity Converge

Prior to starting EduChange, I engaged in rich interdisciplinary design work with a fabulous team of educators, and shared the summary of our successes with the field.

Once established in NYC, EduChange began working with renowned researchers at The Rockefeller University to better understand how 21st-century STEM worked in action, and where it might be headed. This international community boasts more Nobel prizes in Physiology & Medicine than any other in the world, self-organizes to pursue the best questions and, interestingly, does not organize researchers or research into content silos.

In 2001 our Head Scientific Advisor for the USA & Canada, Dr. Sandy Simon, asked this question, “If neither nature, nor science, nor technology is constrained by different disciplines, why is science education still compartmentalized?” To this day, no educational pundit has provided a satisfying reason to maintain the status quo.

With some inspirational success behind us, with a gold standard of scientific R&D for guidance, and with 10 willing public high schools in and beyond NYC, we began to pursue the question.

We initiated a multi-year professional development offering where an EduChange coach visited a single school weekly or biweekly and brought integrated science curricula for teachers to use.

You can learn more about that part of the story here.

As we moved forward into program development, these major drivers guided the designs of our content system:

- Trust nature to deliver the content.

- Trust that what interests STEM professionals also will interest teenagers.

- Contextualize content through STEM stories, and integrate more than science to tell the story as it needs to be told.

- Trust teachers as learners and students as content creators.

- Ensconce content designs in the Information Age, and evolve them accordingly.

Looking back, it appears that two important factors—the time available to teachers & the authenticity of the learning experience—conspired to deliver us to the doorstep of multi-year content integration. With each passing day, I neither regret, nor find evidence to debunk, this design decision.

Suggested Citation: Saldutti, C. (2019, July 7). Changing our relationship with content. 1-2-3 Learn: EduChange Design Blog. https://educhange.com/changing-our-relationship-with-content/

We’ll let you know when the next post is ready for you!